Researchers from the University of Waikato, Earth Sciences New Zealand and the Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha | University of Canterbury have delivered a major scientific advance by creating the first framework to identify short-term reductions in underwater light, described as marine darkwaves. The study shows evidence of sudden and intense darkness events from California to New Zealand that can affect marine ecosystems, providing new insight into how coastal environments respond to rapidly changing conditions, including major events such as Cyclone Gabrielle.

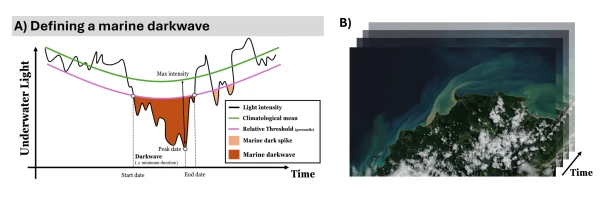

Published in the Nature Portfolio journal Communications Earth & Environment, the research introduces marine darkwaves as an event-based framework for detecting and comparing episodes of unusually low underwater light. While long-term coastal darkening has been documented globally, the study shows that short-lived but intense darkness events can be highly damaging to marine ecosystems and may have ecological impacts that rival longer-term declines in underwater light.

University of Waikato Dr François (Frankie) Thoral

“Light is a fundamental driver of marine productivity all the way up to the upper food chain, yet until now we have not had a consistent way to measure extreme reductions in underwater light, and this phenomenon did not even have a name,” says Dr François (Frankie) Thoral, lead author and marine scientist at Waikato and Canterbury Universities. “Marine darkwaves allow us to identify when and where these events occur, shedding new light on a critical but often overlooked phenomenon.”

The study draws on 16 years of underwater light measurements from California, 10 years of data from New Zealand coastal sites in Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana in the Firth of Thames, at depths of 7 metres and 20 metres, and 21 years of satellite-derived seabed irradiance across the East Cape.

Marine darkwaves across these regions lasted from a few days to more than two months. Some events caused the seabed to receive almost no light compared with normal conditions.

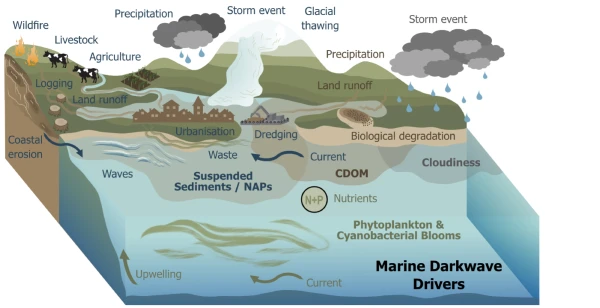

Marine darkwave drivers

Satellite analyses showed between 25 and 80 marine darkwaves along the East Cape since 2002, with many associated with storms, sediment plumes and the coastal impacts of Cyclone Gabrielle. Light recorders at a monitoring buoy at Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana also detected rapid drops in underwater light during storm conditions, showing how quickly these events can form.

“Even short periods of reduced light can impair photosynthesis in kelp forests, seagrass and corals,” says Dr Thoral. “These events can also influence the behaviour of fish, sharks and marine mammals. When darkness persists, the ecological effects can be significant.”

The research is part of longstanding collaborative work between Professor Chris Battershill at the University of Waikato and Distinguished Professor David Schiel from the University of Canterbury, who have worked together across multiple major coastal science programmes in New Zealand. Their joint leadership supports national scale efforts to understand how coastal ecosystems respond to rapid environmental change. The paper also includes international collaborators from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the University of Western Australia.

Defining a marine darkwave

Professor Battershill says the marine darkwave framework provides an essential way to understand rapid environmental change in New Zealand.

“Coastal ecosystems are increasingly exposed to storm-driven sedimentation and higher climate variability,” he says. “Marine darkwaves help us understand when these systems are under acute stress. This framework will be invaluable for iwi and hapū, coastal communities and marine conservationists who need accurate information to guide decision making.”

Professor Schiel notes that “Degradation of many of New Zealand’s coastal kelp forests is increasingly due to sediment run-off from intensified land use, which causes a highly compromised light environment compounded with smothering of habitats. The marine darkwave framework allows an international standard for categorising the underwater light environment and changes over time”.

Although this paper uses long-term datasets from California, New Zealand coastal sites, and satellite observations along the East Cape, related work is underway at Waihau Bay through Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment-funded deployments led by Waikato and Canterbury Universities. These deployments are expanding local monitoring networks and will support future research on marine darkwaves in New Zealand, building on the framework introduced in this study.

Satellite photo post Cyclone Gabrielle

The marine darkwave framework offers a standardised way to compare sudden light reduction events across depths, regions and years. It complements existing tools used to track marine heatwaves, ocean acidification and deoxygenation, and provides a more complete picture of how environmental change affects coastal ecosystems.