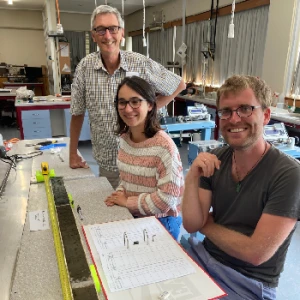

Coring at Lake Rotokaeo (Forest Lake), which was formed about 20,000 years ago. Photo: David G. Schmale III.

In a world-first use of medical imaging technology, scientists have revealed the earthquake-generating potential of faults in the Hamilton and Hauraki areas.

Published today, the study shows that hidden geological faults in Hamilton city, and newly studied faults in the Hauraki district, are capable of generating moderate to large earthquakes, and have done so in the past 15,700 years.

A new liquefaction analysis technique involving multiple lake sediment cores has strong potential for use in other seismically and volcanically active regions, with the ability to detect large prehistoric earthquakes even when the faults that generated them are completely buried.

Use of medical CT technology

The multidisciplinary research team used 3D CT scanning to examine sediment cores extracted from 20,000-year-old lakes scattered throughout the Hamilton Basin.

Sediment cores – tubes of organic-rich mud carefully removed so any layering remains intact – were scanned to reveal distinctive deformation features known as tephra seismites: layers of volcanic ash liquefied during strong earthquakes.

Opened core from Lake Rotokaeo (Forest Lake). L-R: Professor David Lowe, Dr Jordanka Chaneva (formerly University of Waikato PhD student), and Dr Max Kluger. The white ash layer nearest to the camera shows evidence of liquefaction.

CT imaging allowed the seismites to be viewed in their entirety and their dimensions accurately measured, from which a new method of evaluating the earthquake history was developed.

For the first time, researchers provided evidence that at least four active faults in the wider Hamilton-Hauraki area have produced at least five earthquakes over the past 15,700 years. Three of these earthquakes had magnitudes of 7 or greater, with two occurring within the past 1,800 years.

The identified faults include the hidden Kūkūtāruhe and Te Tātua ō Wairere faults in the Hamilton lowlands and the Te Puninga and Kerepehi faults in the Hauraki Plains. The data also suggest a previously unrecognised fault occurs near Te Awamutu.

University of Waikato Emeritus Professor David Lowe says the lake-preserved tephra seismites act like natural seismographs, revealing past quakes and hidden risks.

“Using our new approach, we can detect and date large prehistoric earthquakes even when the faults themselves are completely buried. The known ages on the ash layers allowed us to work out when the earthquakes occurred."

New science with global potential

The research marks the first time the prehistoric earthquake history of the Hamilton Basin has been revealed.

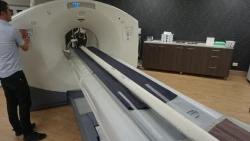

Medical CT scanner operated by radiographer Nic Ross with a lake sediment core on the scan bed ready for scanning.

Professor Lowe says radiographer Nic Ross from I-MED Hamilton Radiology worked with the team to scan 161 sediment cores from 18 lakes, placing them onto a CT scanner bed to generate digital images.

“Our analysis of the cores and scans showed where the strongest ground shaking occurred and allowed us to identify which fault ruptured and when."

Three of the four identified faults ruptured at least once.

The new technique has strong potential for use in other seismically and volcanically active regions, including Auckland, Taranaki–Whanganui, Hawke’s Bay, and internationally in places such as Iceland, Japan, northwestern USA, and central-eastern Europe.

Improving long-term earthquake planning

While Waikato remains a low-to-moderate seismic risk region, the study confirms that strong shaking is possible.

“This doesn’t mean the short-term earthquake risk has increased,” Professor Lowe says. “But it does mean we now understand the long-term hazard much better, and that knowledge helps communities plan, particularly for critical infrastructure such as hospitals, power facilities, and transport networks.

“We haven't changed the hazard since the faults were first discovered in 2015 – we just know more about it. The probability of a large earthquake is relatively low by New Zealand standards, but it is not zero, and risk increases as populations and development expand.”

On average, strong shaking has affected the wider Hamilton–Hauraki region every 3,000 years.

“That doesn’t mean one is about to take place tomorrow – but it does mean the area has a real earthquake history.”

Implications for infrastructure and emergency preparedness

The Hamilton Basin stretches roughly 80 kilometres from Ngāruawāhia to Te Awamutu and about 50 kilometres west to east. It is a major corridor for roads, rail, power, water, and other essential services, and has significant population.

The findings will be added to the New Zealand Community Fault Model, helping long-term seismic hazard planning used for key infrastructure.

Earth Sciences New Zealand earthquake geologist Dr Pilar Villamor, also part of the research team, says events such as the 2010-11 Canterbury earthquakes highlight the risks posed by hidden faults.

“Even though a large earthquake is very unlikely to occur in most people’s lifetimes, Hamiltonians should still be prepared for strong shaking, and having an emergency plan and kit is essential.”

Collaboration, iwi partnership and funding

The four-year project was led by University of Waikato geoscientists Professor Lowe, Dr Max Kluger, Dr Vicki Moon and Dr Tehnuka Ilanko, along with graduate students and collaborators at Earth Sciences New Zealand, the University of Auckland, I-MED Hamilton Radiology, and Swansea University (UK).

The project was supported by iwi including Ngāti Wairere and Ngā Iwi Tōpū o Waipā, as well as local and regional councils and the Department of Conservation.

Funding was provided by the Marsden Fund, MBIE Endeavour Fund, Natural Hazards Commission, MBIE Strategic Science Investment Fund, QuakeCoRE, and Waikato Regional Council.