For University of Waikato graduate Tirama Te Marino Bramley, the spark behind her innovative new environmental app was deeply personal.

Driven to ensure her younger sisters will always have access to their local maunga and freshwater, she set out to create a tool that connects whānau with the knowledge and practices needed to protect and restore their natural environments.

The Bachelor of Design grad has developed an award-winning prototype water-monitoring app grounded in mātauranga Māori.

“I specifically created this app for hapū, Māori communities, iwi and whanau that live in a Pā-like community, where their main source of water is fresh water that runs through their community.”

Tirama Te Marino Bramley.

Senior Lecturer in the School of Design Dr Nicholas (Nic) Vanderschantz, who helped Tirama with her project, says together they focused on context-driven design inspired by the authentic iwi and hapū stories and rich heritage of her whānau.

“As Tirama noted to me early in her ideating, this work is more than human- centred, it is tino rangatiratanga-centred with the goal of restoring authority and decision-making power over their lands and waters to iwi and hapū.”

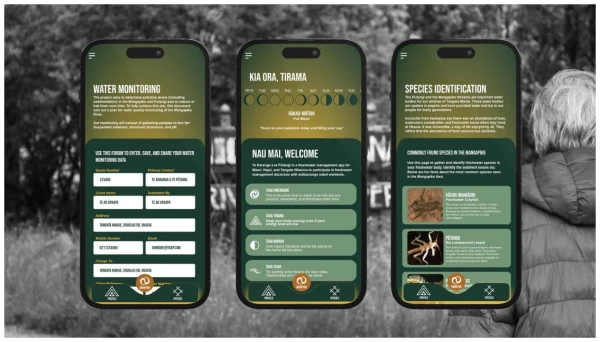

In the app, people will be able to monitor the health of waterways, identify specific species they encounter, and log any pest issues they find.

Tirama (Waikato-Maniapoto, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Porou, Te Arawa) says by placing environmental knowledge back in the hands of whānau and hapū, the app empowers the restoration of waterways and reaffirms of rangatiratanga, with Māori data sovereignty as the basis for lasting ecological and cultural resilience.

She says her inspiration for the app came from time spent in Te Weraiti maunga/mountain, Ōkauia, which is where her younger sisters are from or whakapapa too.

"Unfortunately, at the moment there is mining happening on their maunga which has led to the waterways being dirty. So, we've been working hard to try and stop the mining and find solutions to ensure that the water is fresh and safe to drink.”

The award-winning prototype water-monitoring app is grounded in mātauranga Māori.

Tirama says she created the app to be easy and accessible for whānau, especially those who might not have had the chance to get involved in things like water monitoring, species identification or pest control before.

The app was entered in the Designers Institute of New Zealand Best Design Awards where it won gold in the Student Social Good category.

The judges said it was an “incredibly practical idea” and were surprised that something like this didn’t exist.

They said what stood out was how grounded it felt in mātauranga Māori, while still being thoroughly modern, useful and pragmatic.

The app is designed to be calm, simple, and easy to use. Its colours come from the natural world, the greens and browns of the ngāhere and the blues of the awa.

The icons are inspired by tukutuku patterns and flowing water. Bilingual features make it easy for everyone to use, no matter their age or language level. On the map, users can see live data like temperature, pH, and E. coli, along with tohu from their local environment. Each waterway has its own page, where people can find stories, learn about restoration efforts, and add their own observations.

Tirama is hoping it gets picked up for funding and has pitched it to councils.

In the app, people will be able to monitor the health of waterways, identify specific species they encounter, and log any pest issues they find.

“It’s definitely a tool people are excited about,” says Tirama. “What makes it truly unique is that it’s guided by the maramataka - the Māori lunar calendar. It recognises that some days are best for staying back and observing, while others are perfect for heading out into nature. All of that knowledge will be built into the app too.”

Tirama graduated this month and is currently a graphic designer for Te Wananga Aotearoa.

Dr Vanderschantz also noted the achievement of other design students at the Best Design Awards.

Shania Yates was awarded a silver for her braille and tactile picture book for vision impaired families. Josh Lane received bronze for his youth magazine targeting mental health, and Miriama Royal was a finalist for two physical interactive pop-up picture books that introduce readers to the Māori alphabet.

“Individually developed and self-initiated, the projects challenged students to engage with the United Nations sustainable development goals,” he says.

Dr Vanderschantz highlighted that design awards and competitions serve as an important means of validating students’ learning and achievements. Echoing this view, the newly appointed Head of the School of Design, Professor Ricardo Sosa, explained how such accolades benefit both students and staff.

“For individual students, these awards offer a valuable point of differentiation in their CVs and portfolios. For our staff, the opportunity to mentor and coach students whose work is acknowledged by industry experts is one of the most rewarding aspects of teaching Design.”