Photos of “sinking” Pacific Islands are powerful symbols of climate change, but a University of Waikato researcher says they tell only part of the story, hiding deeper political and economic causes and pushing Pacific peoples’ voices and solutions to the sidelines.

University of Waikato Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations Dr Olli Hellmann is urging news media and the public to rethink how the climate crisis is portrayed, particularly the repeated use of photos showing small Pacific islands as symbols of rising sea levels and vulnerability.

New research published in the Journal of Environmental Media suggests that while iconic images such as polar bears on melting ice or cracked, drought-stricken land are frequently used to illustrate climate change, they are often detached from specific places and people. Instead, they become symbolic of global climate impacts.

Dr Olli Hellmann

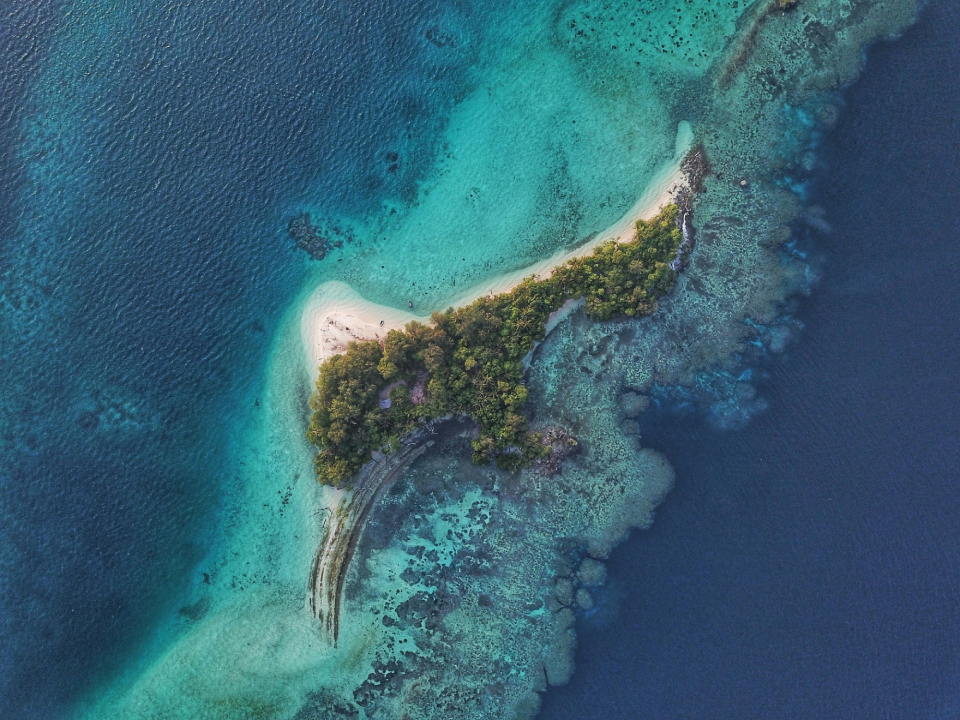

Dr Hellmann’s new research finds that the same logic applies to the Pacific, where photographs of low-lying islands surrounded by vast oceans are routinely used to visualise sea-level rise.

The way these images are framed, particularly through accompanying headlines and stories, shapes how they are understood as symbols of climate change. The same photographs of small Pacific Islands often appear in contexts like tourism advertising, where they are read in completely different ways.

“These kinds of images create the idea that Pacific islands are doomed because of their geography and physical attributes, and that nothing can be done to change their future,” Dr Hellmann says. “They also deflect attention from the political and economic forces driving climate change, making it harder to hold those responsible to account.”

According to Dr Hellmann, iconic images like the polar bear stranded on melting ice often make climate change seem distant and disconnected from everyday life. “When climate change is portrayed as something happening far away in the polar regions, for example, audiences may feel it’s not relevant to their own lives or communities,” he says.

Dr Hellmann adds that the way many of these images are composed can also shape how people respond. “Iconic photographs are frequently taken from afar or from an aerial perspective, presenting climate change as a vast, uncontrollable force,” he says. “That can leave people feeling powerless, as though the problem is too big for individual or collective action to make a difference.”

The second part of his research sees Dr Hellmann explore how a group of young climate activists called the Pacific Climate Warriors use images on Instagram to tell a different story.

“Their photos show young people across the Pacific taking part in protests and climate action, highlighting how the islands are connected through strong cultural and social ties.

“This changes the narrative from one of weakness and isolation to one of strength and action, showing that the real problem is not geography but fossil fuels, and that Pacific Islanders are active leaders in the fight against climate change.”

He says by being shown as strong and resilient in this counter-narrative, they gain the perception of being able to do something about climate change.

Dr Hellmann, who has studied how we communicate visually about the world around us, believes photographs are vital to how people understand climate change.

“It is a slow-moving and often invisible process. If we don’t live in regions already experiencing the impacts of climate change, we may never see it unfolding directly before our eyes.

Chuuk Lagoon in the Pacific Ocean

“That’s why images and so-called photographs of climate change are so significant. They help construct public understanding of the global climate crisis.”

He admits it does start with the photographer but there are other contributors to the problem such as the editor selecting the photo, which is usually the one that will get the most attention.

But Dr Hellmann believes it doesn’t have to be that way.

“There are better images out there. For example, The Guardian has published stories where they have worked with Pacific photographers. Those photos look very different; they often show local communities as resilient and actively finding ways to adapt to or mitigate the impacts of climate change.

“In contrast, the iconic images we usually see are often taken from above or from a distance and rarely include people. So, while more nuanced and empowering photographs do exist, news media still tend to rely on those more problematic images.”