The recent assertion by Dmitry Medvedev, deputy head of Russia’s security council (and former president), that the invasion of Ukraine will “achieve all its goals” and that peace will be “on our terms” raises an obvious question: what are those terms?

History suggests the answer may be a hard one. Modern Russian wars have followed a pattern – victory is either total (Chechnya or Syria) or it involves the dismemberment of the other country (Georgia or Ukraine after the first Russian intervention in 2014).

Peace treaties are rare, and settlements – as Medvedev’s comments implied – have been Russia’s alone to approve. Opponents are expected to surrender, not negotiate.

And right now, Russian President Vladimir Putin may well believe he has the upper hand in Ukraine. Sanctions have hurt but not strangled the Russian economy. Western weapons and intelligence have slowed but not stopped the Russian advance, which grinds on with overwhelming and often indiscriminate use of force.

But with Russia now saying it will expand its war aims, and with the West continuing to pour arms into Ukraine, the risk of the invasion spilling into a larger conflict (by accident or design) slowly grows. Russian threats to European gas supplies during the coming winter suggest both sides are likely to escalate rather than accept defeat.

The only safe way out will be through negotiation. But given what we know about Russian strategies and expectations, how will that be achieved?

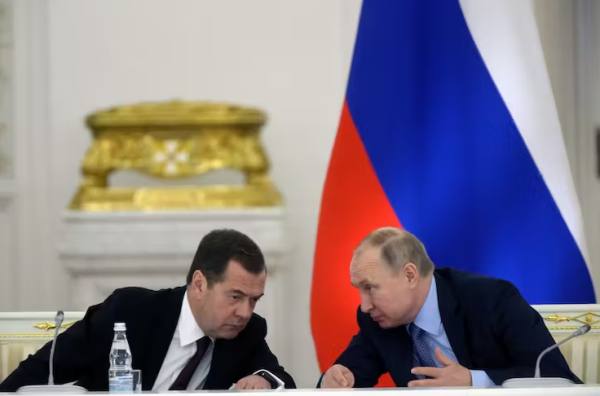

Russia’s terms: Vladimir Putin conferring with then-prime minister Dmitry Medvedev at a State Council meeting at the Kremlin in 2019. Getty Images

What are the bottom lines?

Clearly there is significant uncertainty about what terms Putin might agree to. Given he has denied the existence of Ukrainian statehood at all, he may believe Russia is entitled to it all. Or he may only demand international recognition of Russian claims to territory already conquered.

Beyond that, he may really be looking for the disarmament of all parts of eastern Europe that were once part of the Soviet Union.

While Putin’s bottom lines remain unknown, the onus is now on Ukraine and its Western backers to set out their own terms for what is and isn’t negotiable. Although it may be Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s country at war, ultimately peace will have to be settled by Putin and US President Joe Biden.

There appear to be four main questions that will determine what the bottom lines for peace would look like:

- Should Russia be economically liable for the restoration of the damage caused by its invasion?

- Should those accused of war crimes be brought to justice?

- Should Ukraine’s territorial integrity be retained, or should the country be divided and parts ceded to Russia (as former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger has recommended)?

- What would ongoing security guarantees for the region look like?

What can the West live with?

The fourth question is particularly difficult, given the negligible respect currently shown for international law or treaty commitments.

Rulings by the International Court of Justice that Russia should desist from its invasion of Ukraine have been ignored.

Similarly, the treaties that had previously kept the peace in Europe by slowly building good faith and trust – governing the size of conventional military forces, the prohibition of missile defence shields, the illegality of certain classes of nuclear weapons – are now largely void.

And so we may need to add a final question to that list, perhaps the most significant of all: even if an agreement can be hammered out over Ukraine, will the precedents and perverse incentives it creates be tolerable?

Avoiding something worse

None of this is easy. Compromise, co-operation and peace are, in the end, much harder than war. And there are certainly still many with hawkish views on why Putin must be stopped and his veiled nuclear threats ignored.

But beyond Russia now being considered a significant and direct threat to the security, peace and stability of NATO countries, the wider global context cannot be ignored, either.

In 2021, world military expenditure surpassed US$2 trillion for the first time – 12% more than in 2012. Nuclear arsenals are expanding and upgrading, as are emerging and largely unregulated military technologies in space, cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence and autonomous weapons systems.

Ongoing tensions between China and the West, America, Israel and Iran, and webs of new military alliances (some visible, some opaque) on all sides, all contribute to a world that is becoming less peaceful according to the latest Global Peace Index.

Add to this the real threats to stability from climate change, a global food crisis, stretched supply chains and inflation, and the risk of Ukraine sparking or exacerbating something worse should be clear. Peace on the right terms must be the priority.![]()

Alexander Gillespie, Professor of Law, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.