Shutterstock

Social media has the reputation of being spontaneous, rushed, prone to typos and ungrammatical sentences, and generally a linguistic disaster. And some of it is. However, analysis of Twitter posts on the topic of COVID-19 suggests there is more to social media language than first meets the eye.

While pandemics are not new, COVID-19 is the first to occur in the social media era. Anyone with a device and internet connection has had unlimited access to platforms from which to voice personal opinions and experiences.

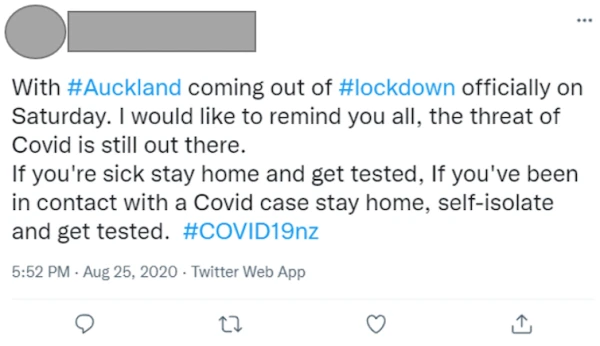

As physical social distancing measures were introduced in 2020, Twitter saw an avalanche of related posts. One of their main characteristics was a predisposition to persuasion: Stay home! End lockdown now! Be kind! I wish everyone stopped hoarding toilet paper! Jacinda needs to lock the borders!

Everyone had an opinion, whether supportive or critical of government policy, including calling for even stronger measures. People were keen not only to share their opinions, but also to convince others and to direct them towards various actions.

But the link between people’s political stance and the language they used to express it wasn’t always what you might expect, as we discovered in our latest research.

Instruction and politeness

The language of persuasion presents an interesting paradox. On the one hand, we want to instruct people and influence them. On the other, no one wants to be told what to do, so we want to maintain harmony and not alienate others.

In English, there is a special grammatical construction whose function is to instruct, known as the “imperative” – for example, “Stay home, save lives”.

But that’s not the only way to instruct. There are more polite and vague alternatives. The strength of the directive can be softened by the use of politeness (“Please stay calm”), or “modal” verbs (“Everyone should stay calm”), or by what are known as “irrealis” constructions (“I wish everyone would stay calm”). Sometimes several strategies can be combined (“Please can everyone stay calm”).

In our recent study, we manually analysed 1,000 tweets from 2020 containing the hashtag #Covid19NZ (or variations of that) to discover which language strategies people employed to persuade others. We also included their political stance – whether they were supportive of government lockdown measures or not.

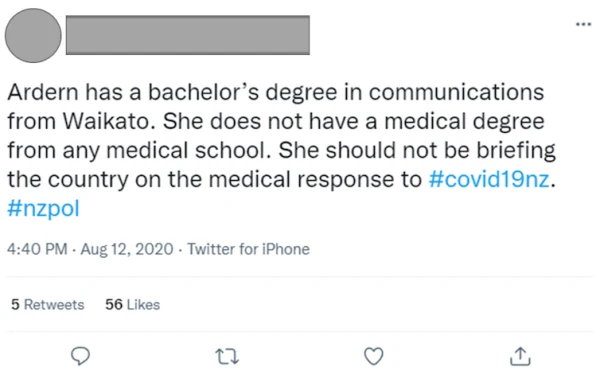

What we found surprised us: users opposed to COVID-19 restrictions who tweeted against government measures took greater care to soften their directives, opting for more polite and vague language; those in support of government actions used more forceful imperatives.

It might seem counter-intuitive that individuals opposing government measures should be so indirect. However, at the time of those initial lockdowns, the majority seemed to accept the sacrifices necessary to protect their own and vulnerable people’s health (we certainly found this in the tweets analysed).

This may explain why those going against the government and perceived popular opinion were being linguistically cautious. They didn’t want to alienate others by appearing too forceful or hotheaded, and so they varied the grammar in their tweets. Such indirect language could also be used for sarcasm and to maintain plausible deniability.

Grammar is more than right or wrong

Grammar is not just about the rules that arise from maintaining consistency within language (for example, subject-verb agreement: “I like grammar, he likes grammar”). Grammar can vary in order to allow for subtlety of expression, too.

The grammatical system presents us with options and has built-in flexibility. Variation is used by speakers to put forward their many opinions, agendas and communication goals in more nuanced ways.

Interestingly, even on a social media platform like Twitter, such nuanced and strategic communication can and does take place. Users may not always plan or edit their posts perfectly, but they are linguistically savvy nonetheless.

We are currently analysing Twitter posts from later in the pandemic, specifically on the topic of vaccines, and the mood has certainly shifted in that time. Both camps appear more aggressive in their directives, less inclined to use indirect language.

As the debate becomes more heated, the stakes rise and there are more opinions in the mix. It’s no longer just about being for or against government measures; support for a measure may not always mean support for the means used to achieve it. Consequently, language strategies are changing too.

For example, an anti-vaccine campaigner writes in their tweet: “Save mothers and babies”. The forceful imperative is more subtle than it first appears, implying that vaccinating children (and their mothers) puts them at risk, without stating what the risk is but hinting it could even be fatal.

As ever, language is a vehicle that divides as well as unites us.

This article was co-written by Jessie Burnette, a Masters Student in English and Linguistics at the University of Waikato.

Andreea S. Calude, Senior Lecturer in Linguistics, University of Waikato

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.